Four wonderful years in Cyprus

The Swedish Cyprus Expedition 1927 - 1931

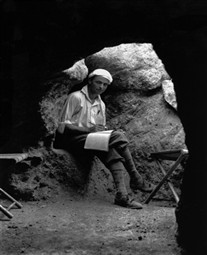

Erick Sjöqvist in Tomb 306.

The Bronze Age chamber-tombs were usually family tombs, used by several generations. There was access to the rock-cut chamber through a passage, called dromos. The tombs often contained pottery and weapons in abundance belonging to the wealthy families of Lapithos.

"The importance of Cypriote civilization is not, however, restricted to its role of intermediator of culture. Cyprus was also a creator of culture and possessed an indigenous civilization which at different times reached a high standard."

(Einar Gjerstad 1948)

In 1923 a young Swedish archaeologist went to Cyprus to study the culture and archaeology of the island. He had been invited by the Swedish consul in Cyprus Luki Z.Pierides, who also was a member of the Archaeological Council of Cyprus. Already in 1922 Luki Z.Pierides had suggested that a Swedish archaeologist should be sent to Cyprus to conduct excavations. The origin of this Expedition was thus closely connected with the Pierides family, since the excavations could start with the initiative of Luki Z.Pierides. And later, during the years of the excavations, the Swedish archaeologists were under his permanent protection

The young Swede not only studied in the museums, but also carried out excavations at Frénaros, Alambra and Kalopsidha and discovered a fortification at Nikolidhes during the year he stayed on the island. The results of his studies were published in his thesis Studies on Prehistoric Cyprus published in 1926, which is still the fundamental work on the Cypriote Bronze Age, although later of course revided.

When Einar Gjerstad - that was the name of the young archaeologist - returned to Sweden, he started preparations for a major archaeological expedition to Cyprus. A committee was formed for the administration of the Expedition under the chairmanship of Crown Prince Gustaf Adolf (later King Gustaf VI Adolf). Private donors gave generous contributions and at the end of the excavations the Swedish State helped to cover additional expenses.

Gjerstad also managed to borrow one of the first automobiles from the director of the Volvo Company, when their production started in 1927. The car was called Jacob and was returned to the director after the excavations had ended four years later. One of these automobiles, is now exhibited in the "Volvo Museum" at Göteborg.

The box with the gold is being sent to Sweden.

In September 1927 the Swedish Cyprus Expedition departed for the island. It included the archaeologists Einar Gjerstad (the head of the Expedition), Alfred Westholm, Erik Sjöqvist and the architect John Lindros. They were all very young, none of them being more than 30 years old. Alfred Westholm was better known as Alfiros, a name which was given to him by the Cypriotes.

The Swedish Cyprus Expedition excavated on a large scale throughout the island between 1927 and 1931. During the incredibly short period of only four years they investigated some 25 sites all over the island. The purpose of the excavations was to establish a chronology for Cypriote archaeology and to shed light on some archaeological problems.

The archaeological remains covered the entire period from the Neolithic to Roman times. The main part of the finds, or about 10,000 vases, derived from nearly 300 rock-cut chamber tombs. Thousands of sculptures were found in sanctuaries or on temple sites. Settlements, fortresses, a royal palace and a Roman theatre also yielded important finds. In addition to pottery and sculpture, objects made of metal, ivory, glass and stone were found. The results of the excavations were published in The Swedish Cyprus Expedition, Vols. I-IV:3 (E.Gjerstad et al.), Stockholm and Lund 1934-1972 (SCE).

The beginning of the excavations

The excavations began in Lapithos in September 1927 where the Swedes excavated a vast Bronze Age necropolis, and in the following year, an important chalcolithic site. Before the excavations could start, some problems remained to be solved...

The excavators tell about a somewhat difficult situation:

”... we had to obtain permission to excavate by signing contracts with all the landowners, and next permit to begin digging was needed from the Government of Cyprus. In sum, many formal obstacles faced us before starting the field work. At a number of sites, the plots of land were small, and in some cases up to a hundred landowners had to be persuaded to sign.”

”It was at Lapithos that we began our work in the autumn of 1927. It was there that our efforts were first rewarded. Lapithos is one of the largest villages in Cyprus and certainly the most beautiful one.”

”When you try to explain to these people that you are not in this venture for profit, that you will not make one penny on the entire venture, but rather will be faced with large expenses instead, you will indicate to them that you are either a liar or a fool.”

The fabulous rich tombs of the wealthy Lapithians and the powerful merchants of Enkomi

The oldest remains uncovered by the Swedes were found on the small rock-island Petra tou Limniti on the north-western coast of Cyprus, where finds from the pre-ceramic Stone Age were discovered. This early period was not previously known in Cyprus. A later phase of the Stone Age, when pottery had replaced the earlier stone vases, was brought to light at Kythrea and at Lapithos in northern Cyprus. Lapithos is also a very important site for tombs from the Cypriote Bronze Age.

The Lapithos tombs have yielded large numbers of tools, swords, daggers and knives with rat-tail tangs, toggle pins, tweezers and rings, cast in red arsenic copper and yellow bronze. They were manufactured c.2000-1800 B.C.

The rich Cypriote copper mines were exploited from ancient to modern times, but it is not yet demonstrated to which extent the native copper of Cyprus was used during the Cypriote Bronze Age.

At Enkomi in eastern Cyprus, rich tombs from the Late Bronze Age containing objects of gold, silver and ivory and hundreds of vases were excavated. In addition to native pottery, a large quantity of Mycenaean pottery was found, showing the Mycenaean activity at the site. Towards the end of the Bronze Age Mycenaean colonists immigrated in different waves to Cyprus. This could be proved through the discovery of chamber tombs of Mycenaean type at Lapithos.

In the Iron Age, starting c. 1050 B.C., the Greek cultural influence was strongest in northern and western Cyprus, at Lapithos and at Marion, while the Phoenicians influenced the southern coast, where the excavations at Amathus and at Kition, the most important Phoenician town in Cyprus, demonstrated the importance of the Phoenician culture on the island.

A unique splint armour, dating from the 6th century B.C., was found at the western acropolis (the Ambelleri) of Idalion. Six thousand eight hundred iron splints, and a few of bronze, formed the body of the armour and were laced to or sewn on a lining of probably cloth or leather. The cuirass was found close to a sanctuary, dedicated to the goddess Athena, the patron goddess of the town.

Also at Stylli in eastern Cyprus, where Crown Prince Gustaf Adolf took part in the excavations, the finds showed relations with the Phoenician culture.

”The walls of the Cypriot rock tombs were not made to suit the height of the Crown Prince and in those tombs where the roof had collapsed and fallen in, filling the chamber with rubble, there was almost only room for his head when he began to empty the tomb.”

(Gjerstad 1933)

The open-air sanctuary at Ajia Iríni

(The name of this site, means ”sacred peace” in Greek.)

The most important find of the Expedition was the discovery of the cult site at Ajia Iríni in northern Cyprus in 1929-1930. Like some other Archaic sanctuaries, it was built over a site dating from the Late Cypriote Bronze Age. About 2000 terracottas were found at Ajia Iríni in their original positions, standing in semicircles around an altar. The terracotta sculptures can be dated to the Cypro-Archaic period, mainly to the years 650-500 B.C.

Most of the terracottas are male figures, but there are also war chariots drawn by horses, riders, ring dancers, bulls and "minotaurs" (a crossbreed of bull and man). The majority of the male figures stand in frontal positions and are dressed in long garments. They also wear helmets or conical caps with cheek-pieces. Many of them are bearded and some wear earrings. A few figures carry votive offerings, while others hold flutes and tambourines. Several terracottas have a lively facial expression and show great individuality.

The sanctuary at Ajia Iríni is characteristic of the rural cult, based on the worship of a divinity of fertility, found in various parts of the island. The god of Ajia Iríni was further connected with cattle and war. The finds belong to the Cypro-Geometric and Cypro-Archaic periods. About half of the figures belong to the Medelhavsmuseet, while the rest are in the Cyprus Museum in Nicosia. In Stockholm, most of them are now exhibited as they were found, grouped around the cult stone, which was found close to the altar and was believed to have inherent powers of fertility.

The site of Ajia Iríni is representative of the cult centres of provincial inland settlements. Distinct from these are the more monumental temples of the towns, for example Kition.

The powerful patron-god of the Kitians

On the acropolis of Kition, the Phoenicians erected a temple to Melqart-Herakles, the patron-god of the town. The first sanctuary consisted of an open temenos area with a roofed cella (the central room in a Greek temple). The open court contained the altar and the votive offerings. All the offerings were found in one pit but can be divided into stylistic groups from the Cypro-Archaic II to the Cypro-Classical I period (c.600-400 B.C.).

The ancient Kitians dedicated votive offerings in limestone to their god, and the sculpture is quite different when compared with that of the small terracottas from Ajia Iríni, made in the "snowman" technique. The cult at Kition was probably of a more official character. The sculpture is more sophisticated, showing influences from both Egypt, Ionia and mainland Greece.

Several statuettes represent Melqart-Herakles himself, dressed in the lion-skin and swinging the mace. The god is represented in a powerful manner, radiating with strength and vitality. Archaic in style, although manufactured 100 years later than similar sculpture in the Greek mainland. Others show female and male votaries with offerings in their hands (a bird or goat) or with hands raised in adoration. Some of the figures are myrtle-wreathed and wear a schematized Greek dress.

The Greek gods Apollo and Athena ruled in the west ...

At Mersinaki, there was an isolated sanctuary site dedicated to Apollo and Athena. A large amount of sculpture from the Cypro-Archaic to the Hellenistic period was found in pits, standing side by side. The votive offerings comprise mostly male statues, but also some female figures, chariot groups and figurines. Nothing, however, remained from the sanctuary proper.

The sculptures are made of limestone or mould-made terracotta. They show a large variety of styles and date from between c.500 and 150 B.C. The art of sculpture during the later periods became merely a traditional handicraft. Many sculptures appear as copies of Greek masterpieces. Famous is the Hellenistic statue of a youth from Mersinaki, somewhat larger than life-size and in pale yellow limestone. His voluminous body forms a great contrast to his weak features and somewhat dreamy gaze. Quite different are the imposing, life-size, terracotta statues, also from Mersinaki but dating from an earlier period. The statues are all men with broad shoulders and stiff attitudes. They wear the Greek chiton and himation and their curly hair and beard are arranged in a Greek fashion, but their frontal position and severe expression are Cypriote. Some of them wear large boots.

A royal palace at Vouní

The most imposing building excavated by the Expedition was the Palace at Vouni, situated on a hill (vounó=mountain in Greek) at a height of 270 m above sea-level at the north-western coast of Cyprus, nearly overlooking Petra tou Limniti.

At Vouní a monumental royal palace was found, built on a mountain high above sea-level. It was in use for more than 100 years and was built in separate stages. The palace was a combination of Cypriote and Greek elements. There are no springs on Vouní, but in the middle of the open court was a cistern fed by rainwater from the roofs.

Remarkable finds were made at Vpuni, mainly limestone statuettes representing young women. Many of them are carrying offerings to the goddess Athena and were found in her temple at the summit of Vouni. A magnificent lif-size head in limestone was also found, today one of the highlights of Medelhavsmuseet.

After each excavation the finds were transported to Nicosia. Here, a "Swedish Institute" (also called the Studio) was established, where the finds were cleaned, restored and examined. In the entrance hall, there was a collection of statues. The work-room was a combined photographic studio, drawing office and study. Another four rooms were filled with antiquities.

The Swedish Cyprus Expedition was the first organized effort to excavate in Cyprus in a scientific manner, for the sake of archaeology and not for private profit which at the time was far too frequent. Many great museums in Europe and the USA have their store-rooms filled with Cypriote antiquities, purchased from foreign diplomats carrying out ”excavations” in Cyprus. These collections have no context recorded, sometimes not even a provenance.

Aftermath

According to the law prevailing at the time, all the finds were divided between Cyprus and Sweden at the end of the excavations during the Spring 1931. Due to the great generosity of the Cypriote authorities, more than half of the finds were allowed to be transported to Sweden. This material now constitute the bulk of the collections in Medelhavsmuseet. A representative part is exhibited in the museum, while the rest is housed in store-rooms.

The Cyprus Collections in the Medelhavsmuseet

The Cyprus Collections in the Medelhavsmuseet are the largest and most important collections of Cypriote antiquities in the world outside Cyprus. There are smaller, but also important collections in the Metropolitan Museum in New York and in the British Museum. These, however, often lack a body of vital information in the shape of scholarly documentation of the find contexts. Therefore the material in the Medelhavsmuseet, together with the relative archives, is an inexhaustible research-source for scholars from all over the world.

The Cyprus Collections consist basically of finds made by the Expedition. The total number of finds from the excavations was c. 18,000, and the number received by the Swedes was about 12,000 or 65%. In addition, there was an extensive sherd material, now kept in 5000 boxes in the storerooms of the Museum. The greater part of this material is now in Stockholm.

The collections of the Medelhavsmuseet include about 7000 Cypriote vases, ranging from Chalcolithic to Roman times and giving a general view of the art and culture of Cyprus in ancient times. A very large collection of magnificent, Red Polished pottery from the important necropolis at Lapithos is eloquent evidence of the skill and imagination of the potters in the Early Cypriote Bronze Age period. Equally grandiose are the much later Mycenaean kraters or wine bowls. These huge and impressive vases come from the rich tombs at Enkomi. Research on the kraters continues, as regards both the place of manufacture and the remarkable decoration.The material also comprises jewelry, glass and a large number of sculptures and artifacts of stone and terracotta. The sculptures which show obvious connections with the Syrio-Anatolian region, and later Egypt and Ionia, are of special interest. Of great importance is also the Hellenistic material, influenced by the sculpture in the artistic centres of Alexandria in Egypt and Pergamon in Asia Minor. The development of the glass industry on the island is illustrated by the Roman glass finds from various sites.

Recent research

Work on the finds from the Swedish excavations did not stop when the excavations were over. Scholars and students from all over the world are still doing research on the material and regularly visit the Cyprus Collections. They examine the material, plans, drawings, notebooks and photographs from different aspects. The immense pottery collection has attracted most of the scholars, but the sculpture, and the rich metal finds from the Lapithos tombs, have also been the foci of much interest.

The Cyprus Collections will long remain a rich source to scholars and students. Pots can still be put together from the immense sherd material. Fragments of sculpture await publication. Many of the already published finds can be re-studied by modern methods and equipment. A major part of the pottery acquired by purchase and through gifts has not been thoroughly studied or published. "... it was indeed rewarding to discover how much knowledge remains hidden in the documents and pottery boxes preserved in the Stockholm museum." (Hult 1992)

Einar Gjerstad was the head of the Expedition. In his book, Ages and days in Cyprus (Engl. transl., 1980), he has not only written a popular account of the excavations but has also given a very lively description of the everyday life of the archaeologists and the Cypriotes they met. The relation is spiced with a lot of humour and anecdotes. The Swedes met many remarkable personages and made friends everywhere.

A quotation from Gjerstad´s book tells of his deep understanding of the possibilities of archaeology:

"... It is clear, then, that an archaeological expedition is not all excavation. It also includes conversations with people living near the excavation sites. When the archaeological investigation has been completed and everybody returns to the kafeneion, then the real talking begins. ... In other words, acquiring a thorough knowledge of the lives of the peasants today ought to enable us to have a psychological understanding of prehistoric events and to understand thoughts which have no written documents to explain them." (Ages and days in Cyprus, p. 78)

An Archaeological Adventure in Cyprus. The Swedish Cyprus Expedition 1927-1931, Stockholm 1997. (Picture-book in English, Swedish and Greek)

This picture-book is published in honour of the Swedish Cyprus Expedition, which started its pioneering excavations in Cyprus in the autumn 1927. The main purpose is to give some glimpses of the everyday life behind the hard work of the scientific excavations carried out by the young Swedish archaeologists, assisted by their many Cypriot friends and workmen. The photographs belong to the archives of the Cyprus collections in Medelhavsmuseet, Stockholm, and are copies from the old glass negatives from the period 1927-1936, including some from the years following the return of the Swedish Cyprus Expedition to Stockholm. Most of the photographs have never been published before. All sites, except three, excavated by the Swedes are situated in the northern part of Cyprus, which for 23 years now has illegaly been occupied by Turkey. Many photographs are therefore important documents of the beautiful and remote parts of the island, now inaccessible to the Greek-Cypriots, their friends and most scholars. Many of the sites are destroyed or transformed into military areas.

The publication of this book has been made possible through the generous contribution from The Pierides Cultural and Scientific Foundation, Larnaca, Cyprus and other sponsors.

Bibliography

Where to read about the The Swedish Cyprus Expedition

Gjerstad, E. et al., The Swedish Cyprus Expedition. Finds and Results of the Excavations in Cyprus 1927-31. Bd I-IV:3. Stockholm, Lund 1934-72.

Gjerstad, E., Ages and Days. SIMA Pocket-book 12. Göteborg 1980.

Hult, G., Nitovikla Reconsidered. (MedMusM, 8). Stockholm 1992.

Hult, G., Nitovikla Reconsidered, in Acta Cypria Part 2, SIMA Pb 117 (ed.P.Åström). Jonsered 1992.

Karageorghis, V., Styrenius, C.-G. and Winbladh, M.-L., Cypriote antiquities in the Medelhavsmuseet (MedMusM, 2), Stockholm 1977.

Rystedt,E.,(ed.) The Swedish Cyprus Expedition. The Living Past. (MedMusM, 9), Stockholm 1994.

Sjöqvist,E., Problems of the Late Cypriote Bronze Age. Stockholm 1940.

Åström,P., Gjerstad,E., Merrillees,R.S., and Westholm,A., ”The Fantastic Years on Cyprus” The Swedish Cyprus Expedition and its Members. Jonsered 1994. SIMA Pocket-book 79.

Marie-Louise Winbladh